- It is a great resource for data analysis, data visualization, data science and machine learning

- It provides many statistical techniques (such as statistical tests, classification, clustering and data reduction)

- It is easy to draw graphs in R, like pie charts, histograms, box plot, scatter plot, etc++

- It works on different platforms (Windows, Mac, Linux)

- It is open-source and free

- It has a large community support

- It has many packages (libraries of functions) that can be used to solve different problems

How to install:

R Syntax

"Hello World!"

5 + 5

‘Hello World!’

10

for (x in 1:10) {

print(x)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10

# This is a comment

print("Hello World!")

[1] "Hello World!"

R Variables

Creating Variables in R

name <- "John"

age <- 40

name # output "John"

age # output 40

‘John’

40

name <- "John Doe"

name # auto-print the value of the name variable

‘John Doe’

for (x in 1:10) {

print(x)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10

Concatenate Elements

text <- "awesome"

paste("R is", text)

‘R is awesome’

text1 <- "R is"

text2 <- "awesome"

paste(text1, text2)

‘R is awesome’

num1 <- 5

num2 <- 10

num1 + num2

15

Multiple Variables

# Assign the same value to multiple variables in one line

var1 <- var2 <- var3 <- "Orange"

# Print variable values

var1

var2

var3

‘Orange’

‘Orange’

‘Orange’

Variable Names (Identifiers)

- A variable can have a short name (like

xandy) or a more descriptive name (age,carname,total_volume). Rules for R variables are: - A variable name must start with a letter and can be a combination of letters, digits, period(

.) - and underscore(

_). If it starts with period(.), it cannot be followed by a digit. - A variable name cannot start with a number or underscore (

_) - Variable names are case-sensitive (

age,AgeandAGEare three different variables) - Reserved words cannot be used as variables (

TRUE,FALSE,NULL,if…)

# Legal variable names:

myvar <- "John"

my_var <- "John"

myVar <- "John"

MYVAR <- "John"

myvar2 <- "John"

.myvar <- "John"

# Illegal variable names:

# 2myvar <- "John"

# my-var <- "John"

# my var <- "John"

# _my_var <- "John"

# my_v@ar <- "John"

# TRUE <- "John"

my_var <- 30 # my_var is type of numeric

my_var <- "Sally" # my_var is now of type character (aka string)

R Basic Data Types

Basic data types in R can be divided into the following types:

numeric- (10.5, 55, 787)integer- (1L, 55L, 100L, where the letter “L” declares this as an integer)complex- (9 + 3i, where “i” is the imaginary part)- character (a.k.a.

string) - (“k”, “R is exciting”, “FALSE”, “11.5”) - logical (a.k.a.

boolean) - (TRUE or FALSE)

We can use the class() function to check the data type of a variable:

# numeric

x <- 10.5

class(x)

# integer

x <- 1000L

class(x)

# complex

x <- 9i + 3

class(x)

# character/string

x <- "R is exciting"

class(x)

# logical/boolean

x <- TRUE

class(x)

‘numeric’

‘integer’

‘complex’

‘character’

‘logical’

R Numbers

There are three number types in R:

- numeric

- integer

- complex

Variables of number types are created when you assign a value to them:

x <- 10.5 # numeric

y <- 10L # integer

z <- 1i # complex

# numeric

x <- 10.5

y <- 55

# Print values of x and y

x

y

# Print the class name of x and y

class(x)

class(y)

10.5

55

‘numeric’

‘numeric’

# integer

x <- 1000L

y <- 55L

# Print values of x and y

x

y

# Print the class name of x and y

class(x)

class(y)

1000

55

‘integer’

‘integer’

# complex

x <- 3+5i

y <- 5i

# Print values of x and y

x

y

# Print the class name of x and y

class(x)

class(y)

3+5i

0+5i

‘complex’

‘complex’

Type Conversion

You can convert from one type to another with the following functions:

as.numeric()as.integer()as.complex()

x <- 1L # integer

y <- 2 # numeric

# convert from integer to numeric:

a <- as.numeric(x)

# convert from numeric to integer:

b <- as.integer(y)

# print values of x and y

x

y

# print the class name of a and b

class(a)

class(b)

1

2

‘numeric’

‘integer’

R Math

Build-in Math Function

max(5, 10, 15)

min(5, 10, 15)

sqrt(16)

abs(-4.7)

ceiling(1.4)

floor(1.4)

15

5

4

4.7

2

1

String Literals

Strings are used for storing text.

A string is surrounded by either single quotation marks, or double quotation marks:

"hello" is the same as 'hello':

# Assign a String to a Variable

str <-"hello"

str

‘hello’

# Multiline string

str <- "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,

consectetur adipiscing elit,

sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt

ut labore et dolore magna aliqua."

str # print the value of str

‘Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,\nconsectetur adipiscing elit,\nsed do eiusmod tempor incididunt\nut labore et dolore magna aliqua.’

However, note that R will add a “\n” at the end of each line break. This is called an escape character, and the n character indicates a new line.

If you want the line breaks to be inserted at the same position as in the code, use the cat() function:

str <- "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,

consectetur adipiscing elit,

sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt

ut labore et dolore magna aliqua."

cat(str)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,

consectetur adipiscing elit,

sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt

ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

String Length

There are many usesful string functions in R.

For example, to find the number of characters in a string, use the nchar() function:

str <- "Hello World!"

nchar(str)

12

Check a String

Use the grepl() function to check if a character or a sequence of characters are present in a string:

str <- "Hello World!"

grepl("H", str)

grepl("Hello", str)

grepl("X", str)

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

Combine Two Strings

Use the paste() function to merge/concatenate two strings:

str1 <- "Hello"

str2 <- "World"

paste(str1, str2)

‘Hello World’

Escape Characters

To insert characters that are illegal in a string, you must use an escape character.

An escape character is a backslash \ followed by the character you want to insert.

An example of an illegal character is a double quote inside a string that is surrounded by double quotes:

str <- "We are the so-called \"Vikings\", from the north."

str

cat(str)

‘We are the so-called “Vikings”, from the north.’

We are the so-called "Vikings", from the north.

Note that auto-printing the str variable will print the backslash in the output. You can use the cat() function to print it without backslash.

Other escape characters in R:

| Code | Result |

|---|---|

\\ |

Backslash |

\n |

New Line |

\r |

Carriage Return |

\t |

Tab |

\b |

Backspace |

R Booleans (Logical Values)

10 > 9 # TRUE because 10 is greater than 9

10 == 9 # FALSE because 10 is not equal to 9

10 < 9 # FALSE because 10 is greater than 9

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

a <- 10

b <- 9

a > b

TRUE

a <- 200

b <- 33

if (b > a) {

print ("b is greater than a")

} else {

print("b is not greater than a")

}

[1] "b is not greater than a"

R Operators

R divides the operators in the following groups:

- Arithmetic operators

- Assignment operators

- Comparison operators

- Logical operators

- Miscellaneous operators

R Arithmetic Operators Arithmetic operators are used with numeric values to perform common mathematical operations:

| Operator | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

+ |

Addition | x + y |

- |

Subtraction | x - y |

* |

Multiplication | x * y |

/ |

Division | x / y |

^ |

Exponent | x ^ y |

%% |

Modulus (Remainder from division) | x %% y |

%/% |

Integer Division | x%/%y |

11+5

11-5

11/5

11^5

11%%5

11%/%5

16

6

2.2

161051

1

2

R Assignment Operators

Assignment operators are used to assign values to variables:

my_var <- 3

my_var <<- 3 # global asigner

3 -> my_var

3 ->> my_var

my_var # print my_var

3

R Comparison Operators

Comparison operators are used to compare two values:

| Operator | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

== |

Equal | x == y |

!= |

Not equal | x != y |

> |

Greater than | x > y |

< |

Less than | x < y |

>= |

Greater than or equal to | x >= y |

<= |

Less than or equal to | x <= y |

R Logical Operators

Logical operators are used to combine conditional statements:

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

& |

Element-wise Logical AND operator. It returns TRUE if both elements are TRUE | |

&& |

Logical AND operator - Returns TRUE if both statements are TRUE | |

| |

Elementwise- Logical OR operator. It returns TRUE if one of the statement is TRUE | |

|| |

Logical OR operator. It returns TRUE if one of the statement is TRUE. | |

! |

Logical NOT - returns FALSE if statement is TRUE |

R Miscellaneous Operators Miscellaneous operators are used to manipulate data:

- Operator Description Example

- Creates a series of numbers in a sequence x <- 1:10 %in% Find out if an element belongs to a vector x %in% y %% Matrix Multiplication x <- Matrix1 %% Matrix2

R Logical Operators

Logical operators are used to combine conditional statements:

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

& |

Element-wise Logical AND operator. It returns TRUE if both elements are TRUE | |

&& |

Logical AND operator - Returns TRUE if both statements are TRUE | |

\| |

Elementwise- Logical OR operator. It returns TRUE if one of the statement is TRUE | |

\|\| |

Logical OR operator. It returns TRUE if one of the statement is TRUE | |

! |

Logical NOT - returns FALSE if statement is TRUE |

R Miscellaneous Operators

Miscellaneous operators are used to manipulate data:

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

: |

Creates a series of numbers in a sequence | x <- 1:10 |

%in% |

Find out if an element belongs to a vector | x %in% y |

%*% |

Matrix Multiplication | x <- Matrix1 %*% Matrix2 |

The if, if…else Statement

a <- 33

b <- 200

if (b > a) {

print("b is greater than a")

}

[1] "b is greater than a"

a <- 33

b <- 33

if (b > a) {

print("b is greater than a")

} else if (a == b) {

print ("a and b are equal")

}

[1] "a and b are equal"

a <- 200

b <- 33

if (b > a) {

print("b is greater than a")

} else if (a == b) {

print("a and b are equal")

} else {

print("a is greater than b")

}

[1] "a is greater than b"

Nested If Statements

x <- 41

if (x > 10) {

print("Above ten")

if (x > 20) {

print("and also above 20!")

} else {

print("but not above 20.")

}

} else {

print("below 10.")

}

[1] "Above ten"

[1] "and also above 20!"

a <- 200

b <- 33

c <- 500

if (a > b & c > a) {

print("Both conditions are true")

}

[1] "Both conditions are true"

a <- 200

b <- 33

c <- 500

if (a > b | a > c) {

print("At least one of the conditions is true")

}

[1] "At least one of the conditions is true"

Loops

Loops can execute a block of code as long as a specified condition is reached.

Loops are handy because they save time, reduce errors, and they make code more readable.

R has two loop commands:

- while loops

- for loops

while loops

i <- 1

while (i < 6) {

print(i)

i <- i + 1

}

print(i)

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

# break

i <- 1

while (i < 6) {

print(i)

i <- i + 1

if (i == 4) {

break

}

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

# next

i <- 0

while (i < 6) {

i <- i + 1

if (i == 3) {

next

}

print(i)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

dice <- 1

while (dice <= 6) {

if (dice < 6) {

print("No Yahtzee")

} else {

print("Yahtzee!")

}

dice <- dice + 1

}

[1] "No Yahtzee"

[1] "No Yahtzee"

[1] "No Yahtzee"

[1] "No Yahtzee"

[1] "No Yahtzee"

[1] "Yahtzee!"

for loops

for (x in 1:10) {

print(x)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10

fruits <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for (x in fruits) {

print(x)

}

[1] "apple"

[1] "banana"

[1] "cherry"

dice <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

for (x in dice) {

print(x)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

# break

fruits <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for (x in fruits) {

if (x == "cherry") {

break

}

print(x)

}

[1] "apple"

[1] "banana"

# next

fruits <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for (x in fruits) {

if (x == "banana") {

next

}

print(x)

}

[1] "apple"

[1] "cherry"

dice <- 1:6

for(x in dice) {

if (x == 6) {

print(paste("The dice number is", x, "Yahtzee!"))

} else {

print(paste("The dice number is", x, "Not Yahtzee"))

}

}

[1] "The dice number is 1 Not Yahtzee"

[1] "The dice number is 2 Not Yahtzee"

[1] "The dice number is 3 Not Yahtzee"

[1] "The dice number is 4 Not Yahtzee"

[1] "The dice number is 5 Not Yahtzee"

[1] "The dice number is 6 Yahtzee!"

# Nested loops

adj <- list("red", "big", "tasty")

fruits <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for (x in adj) {

for (y in fruits) {

print(paste(x, y))

}

}

[1] "red apple"

[1] "red banana"

[1] "red cherry"

[1] "big apple"

[1] "big banana"

[1] "big cherry"

[1] "tasty apple"

[1] "tasty banana"

[1] "tasty cherry"

Function

Creating a Function

To create a function, use the function() keyword:

my_function <- function() { # create a function with the name my_function

print("Hello World!")

}

my_function() # call the function named my_function

[1] "Hello World!"

my_function <- function(fname) {

paste(fname, "Griffin")

}

my_function("Peter")

my_function("Lois")

my_function("Stewie")

‘Peter Griffin’

‘Lois Griffin’

‘Stewie Griffin’

Number of Arguments

By default, a function must be called with the correct number of arguments. Meaning that if your function expects 2 arguments, you have to call the function with 2 arguments, not more, and not less (otherwise you will get an error):

my_function <- function(fname, lname) {

paste(fname, lname)

}

my_function("Peter", "Griffin")

‘Peter Griffin’

Default parameter value

my_function <- function(country = "Norway") {

paste("I am from", country)

}

my_function("Sweden")

my_function("India")

my_function() # will get the default value, which is Norway

my_function("USA")

‘I am from Sweden’

‘I am from India’

‘I am from Norway’

‘I am from USA’

Return values

my_function <- function(x) {

return (5 * x)

}

print(my_function(3))

print(my_function(5))

print(my_function(9))

[1] 15

[1] 25

[1] 45

Nested Functions

There are two ways to create a nested function:

- Call a function within another function.

- Write a function within a function.

Call a function within another function

Nested_function <- function(x, y) {

a <- x + y

return(a)

}

Nested_function(Nested_function(2,2), Nested_function(3,3))

10

Write a function within a function

Outer_func <- function(x) {

Inner_func <- function(y) {

a <- x + y

return(a)

}

return (Inner_func)

}

output <- Outer_func(3) # To call the Outer_func

output(5)

8

Recursion

tri_recursion <- function(k) {

if (k > 0) {

result <- k + tri_recursion(k - 1)

print(result)

} else {

result = 0

return(result)

}

}

tri_recursion(6)

[1] 1

[1] 3

[1] 6

[1] 10

[1] 15

[1] 21

Global variables

txt <- "awesome"

my_function <- function() {

paste("R is", txt)

}

my_function()

‘R is awesome’

txt <- "global variable"

my_function <- function() {

txt = "fantastic"

paste("R is", txt)

}

my_function()

txt # print txt

‘R is fantastic’

‘global variable’

The Global Assignment Operator

Normally, when you create a variable inside a function, that variable is local, and can only be used inside that function.

To create a global variable inside a function, you can use the global assignment operator <<-

# If you use the assignment operator <<-, the variable belongs to the global scope:

my_function <- function() {

txt <<- "fantastic"

paste("R is", txt)

}

my_function()

print(txt)

‘R is fantastic’

[1] "fantastic"

# Also, use the global assignment operator if you want to change a global variable inside a function:

txt <- "awesome"

my_function <- function() {

txt <<- "fantastic"

paste("R is", txt)

}

my_function()

paste("R is", txt)

‘R is fantastic’

‘R is fantastic’

R DATA STRUCTURE

Vector

# Vector of strings

fruits <- c("banana", "apple", "orange")

# Print fruits

fruits

length(fruits)

# Vector of numerical values

numbers <- c(1, 2, 3)

# Print numbers

numbers

# Vector with numerical decimals in a sequence

numbers1 <- 1.5:6.5

numbers1

# Vector with numerical decimals in a sequence where the last element is not used

numbers2 <- 1.5:6.3

numbers2

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘banana’</li><li>‘apple’</li><li>‘orange’</li></ol>

3

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>1.5</li><li>2.5</li><li>3.5</li><li>4.5</li><li>5.5</li><li>6.5</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>1.5</li><li>2.5</li><li>3.5</li><li>4.5</li><li>5.5</li></ol>

fruits <- c("banana", "apple", "orange", "mango", "lemon")

numbers <- c(13, 3, 5, 7, 20, 2)

sort(fruits) # Sort a string

sort(numbers) # Sort numbers

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘apple’</li><li>‘banana’</li><li>‘lemon’</li><li>‘mango’</li><li>‘orange’</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>5</li><li>7</li><li>13</li><li>20</li></ol>

fruits[1]

fruits[c(1,4)]

# Access all items except for the first item

fruits[c(-1)]

‘banana’

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘banana’</li><li>‘mango’</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘apple’</li><li>‘orange’</li><li>‘mango’</li><li>‘lemon’</li></ol>

# Change "banana" to "pear"

fruits[1] <- "pear"

# Print fruits

fruits

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘pear’</li><li>‘apple’</li><li>‘orange’</li><li>‘mango’</li><li>‘lemon’</li></ol>

repeat_each <- rep(c(1,2,3), each = 3)

repeat_each

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>2</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>3</li><li>3</li></ol>

repeat_times <- rep(c(1,2,3), times = 3)

repeat_times

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li></ol>

repeat_indepent <- rep(c(1,2,3), times = c(5,2,1))

repeat_indepent

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>2</li><li>3</li></ol>

numbers <- seq(from = 0, to = 100, by = 20)

numbers

<ol class=list-inline><li>0</li><li>20</li><li>40</li><li>60</li><li>80</li><li>100</li></ol>

List

A list in R can contain many different data types inside it. A list is a collection of data which is ordered and changeable.

# List of strings

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

# Print the list

thislist

- 'apple'

- 'banana'

- 'cherry'

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

thislist[1] <- "blackcurrant"

# Print the updated list

thislist

- 'blackcurrant'

- 'banana'

- 'cherry'

length(thislist)

3

"apple" %in% thislist

FALSE

append(thislist, "orange")

- 'blackcurrant'

- 'banana'

- 'cherry'

- 'orange'

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

append(thislist, "orange", after = 2)

- 'apple'

- 'banana'

- 'orange'

- 'cherry'

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

newlist <- thislist[-1]

# Print the new list

newlist

- 'banana'

- 'cherry'

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange", "kiwi", "melon", "mango")

(thislist)[2:5]

- 'banana'

- 'cherry'

- 'orange'

- 'kiwi'

thislist <- list("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for (x in thislist) {

print(x)

}

[1] "apple"

[1] "banana"

[1] "cherry"

list1 <- list("a", "b", "c")

list2 <- list(1,2,3)

list3 <- c(list1,list2)

list3

- 'a'

- 'b'

- 'c'

- 1

- 2

- 3

Matrices

# Create a matrix

thismatrix <- matrix(c(1,2,3,4,5,6), nrow = 3, ncol = 2)

# Print the matrix

thismatrix

| 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 6 |

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange"), nrow = 2, ncol = 2)

thismatrix

| apple | cherry |

| banana | orange |

thismatrix[1, 2]

‘cherry’

thismatrix[, 2]

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘cherry’</li><li>‘orange’</li></ol>

thismatrix[2,]

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘banana’</li><li>‘orange’</li></ol>

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange","grape", "pineapple", "pear", "melon", "fig"), nrow = 3, ncol = 3)

thismatrix

| apple | orange | pear |

| banana | grape | melon |

| cherry | pineapple | fig |

thismatrix[c(1,2),]

| apple | orange | pear |

| banana | grape | melon |

thismatrix[, c(1,2)]

| apple | orange |

| banana | grape |

| cherry | pineapple |

Add rows or columns

# add rows or columns

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange","grape", "pineapple", "pear", "melon", "fig"), nrow = 3, ncol = 3)

newmatrix <- cbind(thismatrix, c("strawberry", "blueberry", "raspberry"))

# Print the new matrix

newmatrix

| apple | orange | pear | strawberry |

| banana | grape | melon | blueberry |

| cherry | pineapple | fig | raspberry |

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange","grape", "pineapple", "pear", "melon", "fig"), nrow = 3, ncol = 3)

newmatrix <- rbind(thismatrix, c("strawberry", "blueberry", "raspberry"))

# Print the new matrix

newmatrix

| apple | orange | pear |

| banana | grape | melon |

| cherry | pineapple | fig |

| strawberry | blueberry | raspberry |

Remove rows or columns

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange", "mango", "pineapple"), nrow = 3, ncol =2)

thismatrix

| apple | orange |

| banana | mango |

| cherry | pineapple |

#Remove the first row and the first column

thismatrix <- thismatrix[-c(1),-c(1)]

thismatrix

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘mango’</li><li>‘pineapple’</li></ol>

thismatrix <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "orange"), nrow = 2, ncol = 2)

"apple" %in% thismatrix

TRUE

dim(thismatrix)

<ol class=list-inline><li>2</li><li>2</li></ol>

length(thismatrix)

4

for (rows in 1:nrow(thismatrix)) {

for (columns in 1:ncol(thismatrix)) {

print(thismatrix[rows, columns])

}

}

[1] "apple"

[1] "cherry"

[1] "banana"

[1] "orange"

# Combine matrices

Matrix1 <- matrix(c("apple", "banana", "cherry", "grape"), nrow = 2, ncol = 2)

Matrix2 <- matrix(c("orange", "mango", "pineapple", "watermelon"), nrow = 2, ncol = 2)

# Adding it as a rows

Matrix_Combined <- rbind(Matrix1, Matrix2)

Matrix_Combined

# Adding it as a columns

Matrix_Combined <- cbind(Matrix1, Matrix2)

Matrix_Combined

| apple | cherry |

| banana | grape |

| orange | pineapple |

| mango | watermelon |

| apple | cherry | orange | pineapple |

| banana | grape | mango | watermelon |

Arrays

- Compared to matrices, arrays can have more than two dimensions. (something like the tensors)

- Arrays can only have one data type.

# An array with one dimension with values ranging from 1 to 24

thisarray <- c(1:24)

thisarray

# An array with more than one dimension

multiarray <- array(thisarray, dim = c(4, 3, 2))

multiarray

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>4</li><li>5</li><li>6</li><li>7</li><li>8</li><li>9</li><li>10</li><li>11</li><li>12</li><li>13</li><li>14</li><li>15</li><li>16</li><li>17</li><li>18</li><li>19</li><li>20</li><li>21</li><li>22</li><li>23</li><li>24</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>4</li><li>5</li><li>6</li><li>7</li><li>8</li><li>9</li><li>10</li><li>11</li><li>12</li><li>13</li><li>14</li><li>15</li><li>16</li><li>17</li><li>18</li><li>19</li><li>20</li><li>21</li><li>22</li><li>23</li><li>24</li></ol>

multiarray[2, 3, 2]

22

multiarray[c(1),,1]

multiarray[,c(1),1]

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>5</li><li>9</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>1</li><li>2</li><li>3</li><li>4</li></ol>

2 %in% multiarray

dim(multiarray)

length(multiarray)

TRUE

<ol class=list-inline><li>4</li><li>3</li><li>2</li></ol>

24

for(x in multiarray){

print(x)

}

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10

[1] 11

[1] 12

[1] 13

[1] 14

[1] 15

[1] 16

[1] 17

[1] 18

[1] 19

[1] 20

[1] 21

[1] 22

[1] 23

[1] 24

Data Frames

Data Frames are data displayed in a format as a table.

Data Frames can have different types of data inside it. While the first column can be character, the second and third can be numeric or logical. However, each column should have the same type of data.

Use the data.frame() function to create a data frame:

# Create a data frame

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

# Print the data frame

Data_Frame

| Training | Pulse | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 |

| Other | 120 | 45 |

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

Data_Frame

summary(Data_Frame)

| Training | Pulse | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 |

| Other | 120 | 45 |

Training Pulse Duration

Length:3 Min. :100.0 Min. :30.0

Class :character 1st Qu.:110.0 1st Qu.:37.5

Mode :character Median :120.0 Median :45.0

Mean :123.3 Mean :45.0

3rd Qu.:135.0 3rd Qu.:52.5

Max. :150.0 Max. :60.0

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

Data_Frame[1]

Data_Frame[["Training"]]

Data_Frame$Training

| Training |

|---|

| <chr> |

| Strength |

| Stamina |

| Other |

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘Strength’</li><li>‘Stamina’</li><li>‘Other’</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘Strength’</li><li>‘Stamina’</li><li>‘Other’</li></ol>

Add rows

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

# Add a new row

New_row_DF <- rbind(Data_Frame, c("Strength", 110, 110))

# Print the new row

New_row_DF

| Training | Pulse | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <chr> | <chr> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 |

| Other | 120 | 45 |

| Strength | 110 | 110 |

Add columns

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

# Add a new column

New_col_DF <- cbind(Data_Frame, Steps = c(1000, 6000, 2000))

# Print the new column

New_col_DF

| Training | Pulse | Duration | Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 | 1000 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 | 6000 |

| Other | 120 | 45 | 2000 |

Remove rows and cols

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

# Remove the first row and column

Data_Frame_New <- Data_Frame[-c(1), -c(1)]

# Print the new data frame

Data_Frame_New

| Pulse | Duration | |

|---|---|---|

| <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| 2 | 150 | 30 |

| 3 | 120 | 45 |

Dim

Data_Frame <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

dim(Data_Frame)

ncol(Data_Frame)

nrow(Data_Frame)

length(Data_Frame)

<ol class=list-inline><li>3</li><li>3</li></ol>

3

3

3

Combining Dataframes in col dim or in row dim

Data_Frame1 <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

Data_Frame2 <- data.frame (

Training = c("Stamina", "Stamina", "Strength"),

Pulse = c(140, 150, 160),

Duration = c(30, 30, 20)

)

New_Data_Frame <- rbind(Data_Frame1, Data_Frame2)

New_Data_Frame

| Training | Pulse | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 |

| Other | 120 | 45 |

| Stamina | 140 | 30 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 |

| Strength | 160 | 20 |

Data_Frame3 <- data.frame (

Training = c("Strength", "Stamina", "Other"),

Pulse = c(100, 150, 120),

Duration = c(60, 30, 45)

)

Data_Frame4 <- data.frame (

Steps = c(3000, 6000, 2000),

Calories = c(300, 400, 300)

)

New_Data_Frame1 <- cbind(Data_Frame3, Data_Frame4)

New_Data_Frame1

| Training | Pulse | Duration | Steps | Calories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Strength | 100 | 60 | 3000 | 300 |

| Stamina | 150 | 30 | 6000 | 400 |

| Other | 120 | 45 | 2000 | 300 |

Factors

Factors are used to categorize data. Examples of factors are:

- Demography: Male/Female

- Music: Rock, Pop, Classic, Jazz

- Training: Strength, Stamina

To create a factor, use the

factor()function and add a vector as argument:

# Create a factor

music_genre <- factor(c("Jazz", "Rock", "Classic", "Classic", "Pop", "Jazz", "Rock", "Jazz"))

# Print the factor

music_genre

<ol class=list-inline><li>Jazz</li><li>Rock</li><li>Classic</li><li>Classic</li><li>Pop</li><li>Jazz</li><li>Rock</li><li>Jazz</li></ol>

music_genre <- factor(c("Jazz", "Rock", "Classic", "Classic", "Pop", "Jazz", "Rock", "Jazz"), levels = c("Classic", "Jazz", "Pop", "Rock", "Other"))

levels(music_genre)

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘Classic’</li><li>‘Jazz’</li><li>‘Pop’</li><li>‘Rock’</li><li>‘Other’</li></ol>

length(music_genre)

8

music_genre[3]

Classic

music_genre <- factor(c("Jazz", "Rock", "Classic", "Classic", "Pop", "Jazz", "Rock", "Jazz"))

music_genre[3] <- "Pop"

music_genre[3]

Pop

Note that you cannot change the value of a specific item if it is not already specified in the factor. The following example will produce an error:

music_genre <- factor(c("Jazz", "Rock", "Classic", "Classic", "Pop", "Jazz", "Rock", "Jazz"))

music_genre[3] <- "Opera"

music_genre[3]

However, if you have already specified it inside the levels argument, it will work:

music_genre <- factor(c("Jazz", "Rock", "Classic", "Classic", "Pop", "Jazz", "Rock", "Jazz"), levels = c("Classic", "Jazz", "Pop", "Rock", "Opera"))

music_genre[3] <- "Opera"

music_genre[3]

Opera

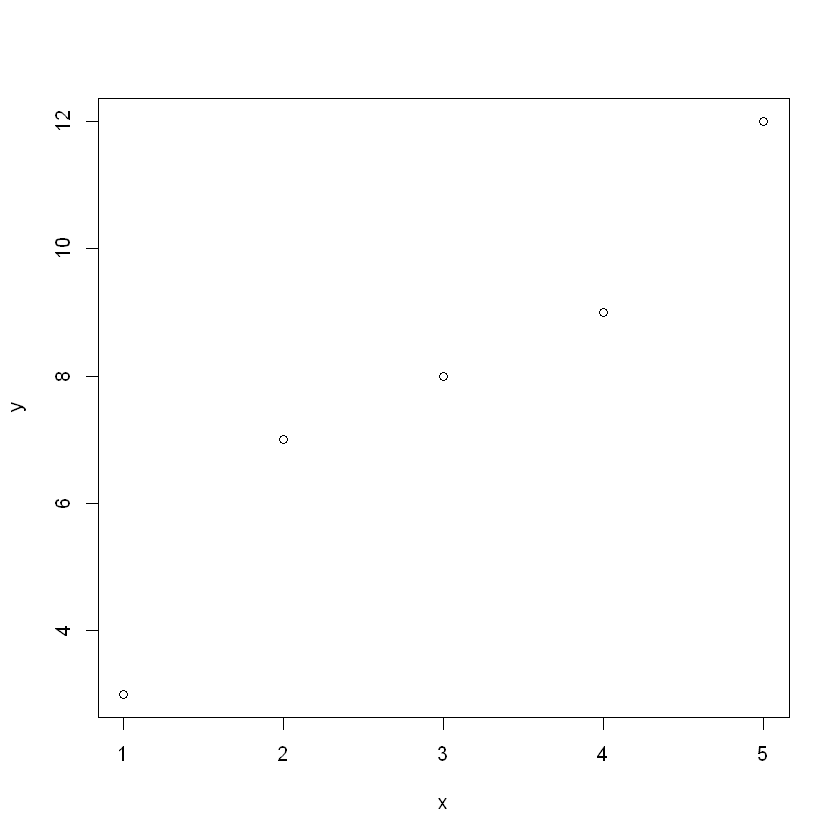

GRAPHIC AND DATA VISUALIZATION

Simple plot

plot(1,3)

plot(c(1, 8), c(3, 10))

plot(c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5), c(3, 7, 8, 9, 12))

plot(1:10)

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

y <- c(3, 7, 8, 9, 12)

plot(x, y)

plot(1:10, type="l")

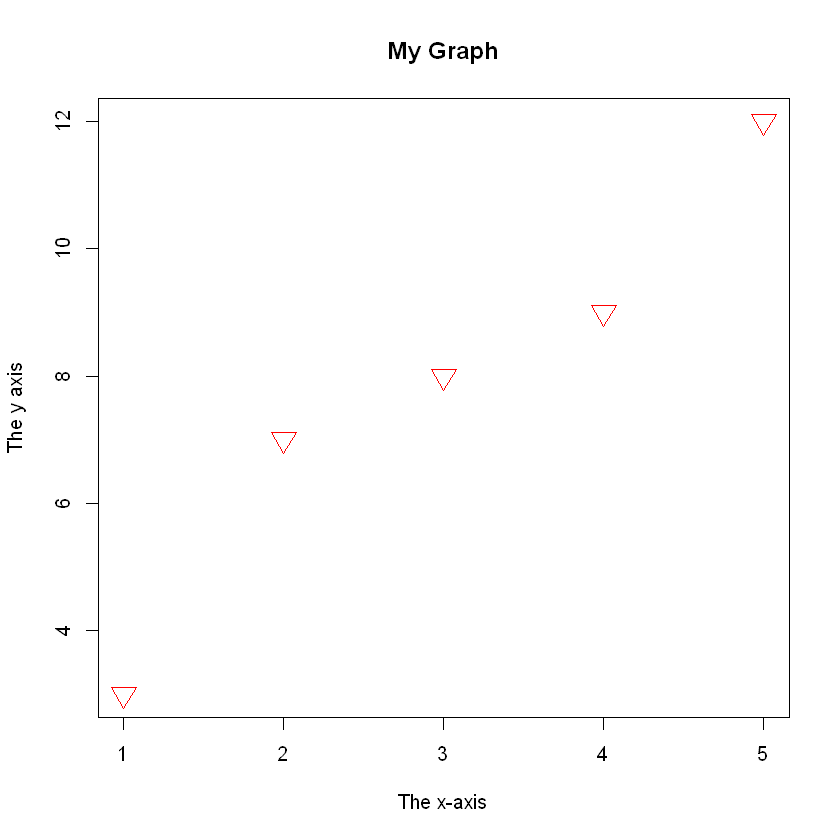

plot(x,y, main="My Graph", col="red", pch=25, cex=2, xlab="The x-axis", ylab="The y axis")

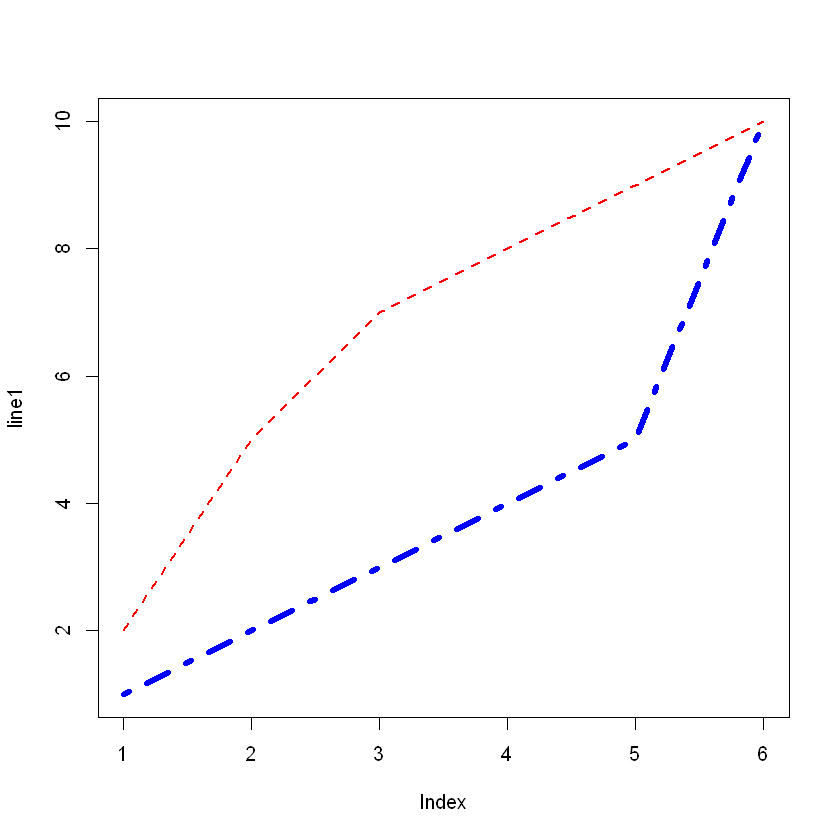

Line

plot(1:10, type="l", col="blue", lwd=5, lty = 6)

line1 <- c(1,2,3,4,5,10)

line2 <- c(2,5,7,8,9,10)

plot(line1, type = "l", col = "blue", lwd=5, lty =4)

lines(line2, type="l", col = "red", lwd=2, lty = 2)

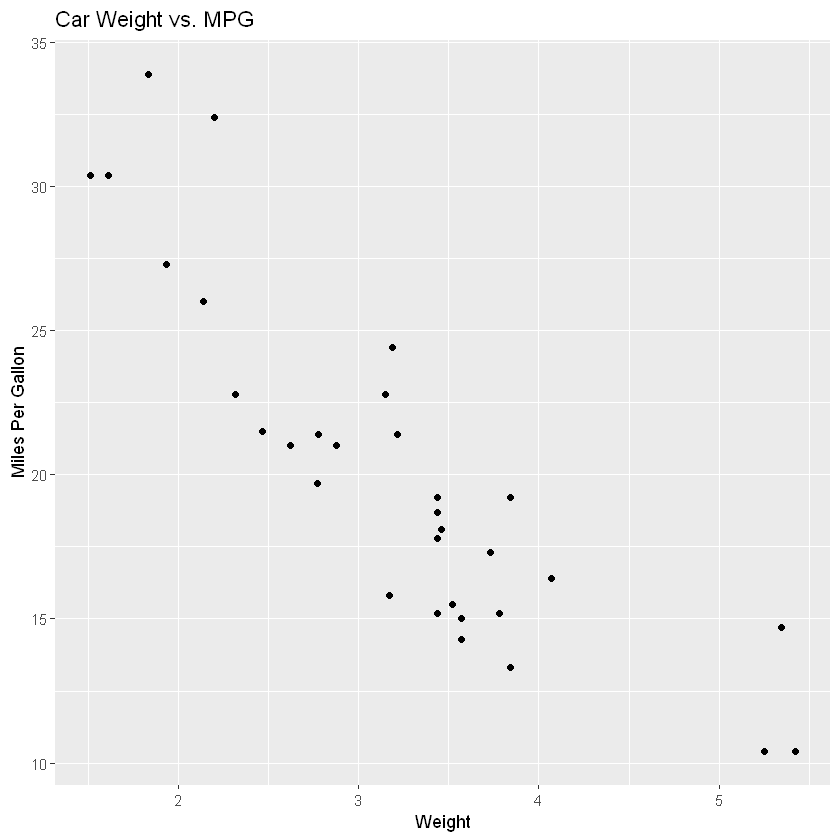

# Load the required library

library(ggplot2)

# Customizing the ggplot

ggplot(data = mtcars, aes(x = wt, y = mpg)) +

geom_point() +

ggtitle("Car Weight vs. MPG") +

xlab("Weight") +

ylab("Miles Per Gallon")

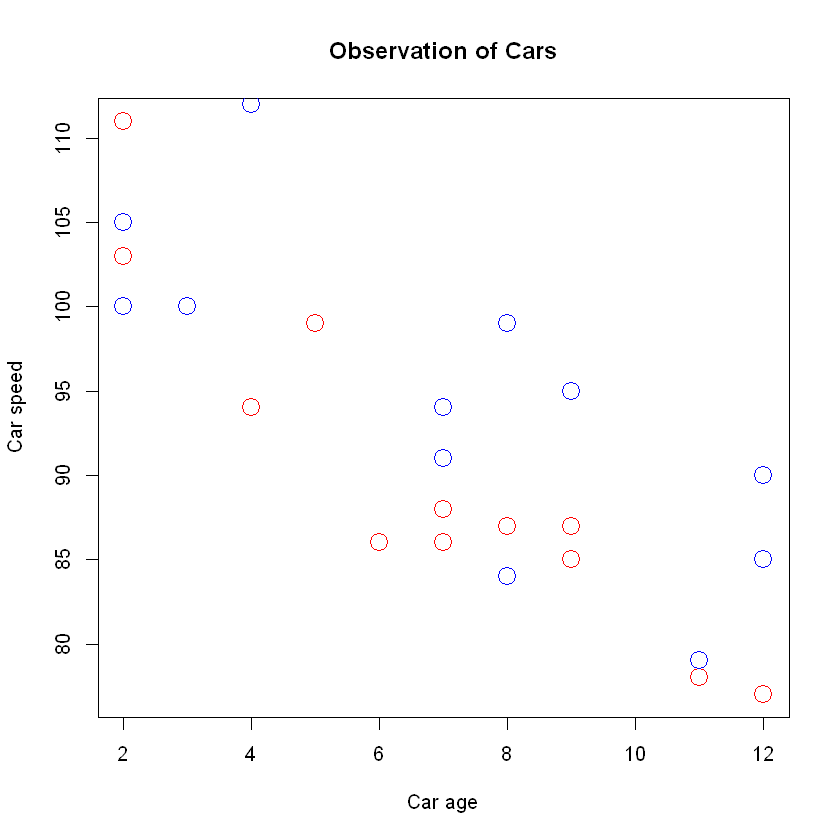

Scatter plots

# day one, the age and speed of 12 cars:

x1 <- c(5,7,8,7,2,2,9,4,11,12,9,6)

y1 <- c(99,86,87,88,111,103,87,94,78,77,85,86)

# day two, the age and speed of 15 cars:

x2 <- c(2,2,8,1,15,8,12,9,7,3,11,4,7,14,12)

y2 <- c(100,105,84,105,90,99,90,95,94,100,79,112,91,80,85)

plot(x1, y1, main="Observation of Cars", xlab="Car age", ylab="Car speed", col="red", cex=2)

points(x2, y2, col="blue", cex=2)

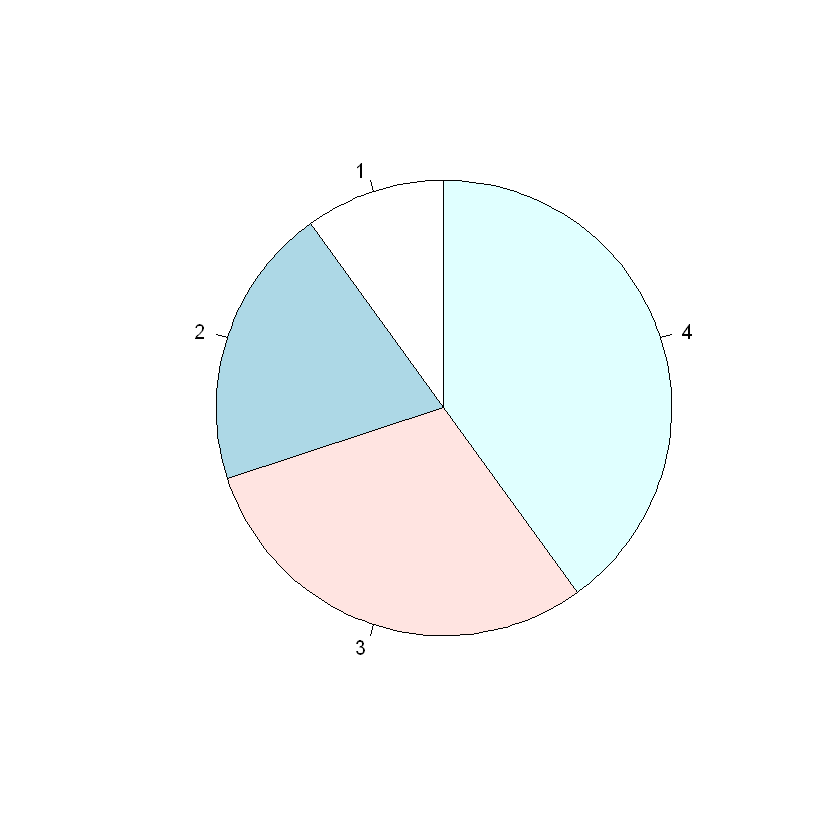

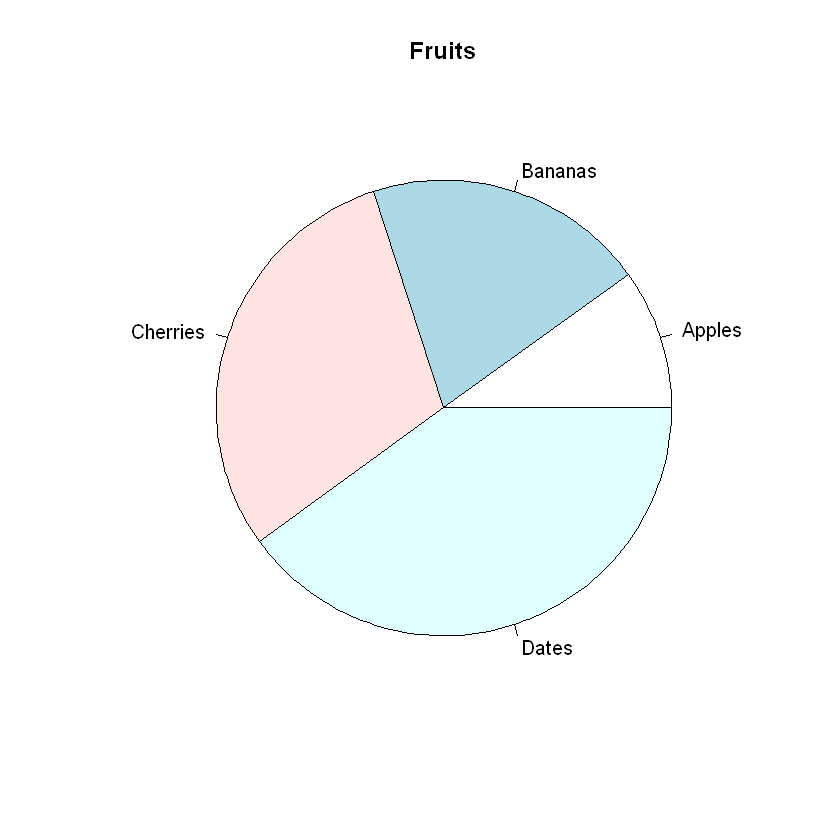

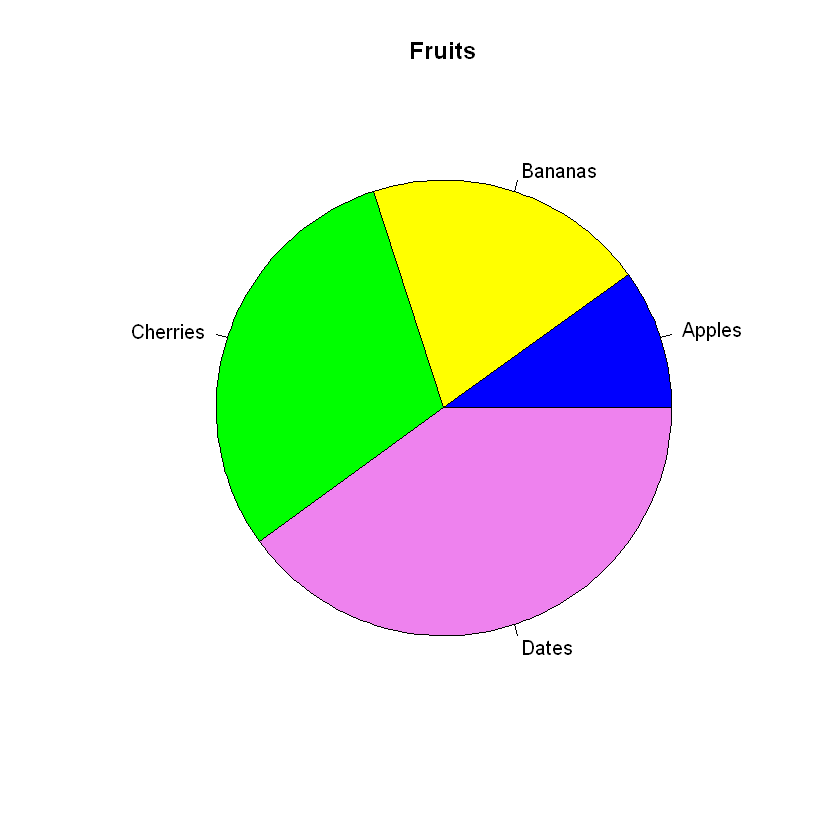

Pie Charts

# Create a vector of pies

x <- c(10,20,30,40)

# Display the pie chart and start the first pie at 90 degrees

pie(x, init.angle = 90)

# Create a vector of pies

x <- c(10,20,30,40)

# Create a vector of labels

mylabel <- c("Apples", "Bananas", "Cherries", "Dates")

# Display the pie chart with labels

pie(x, label = mylabel, main = "Fruits")

# Create a vector of colors

colors <- c("blue", "yellow", "green", "violet")

# Display the pie chart with colors

pie(x, label = mylabel, main = "Fruits", col = colors)

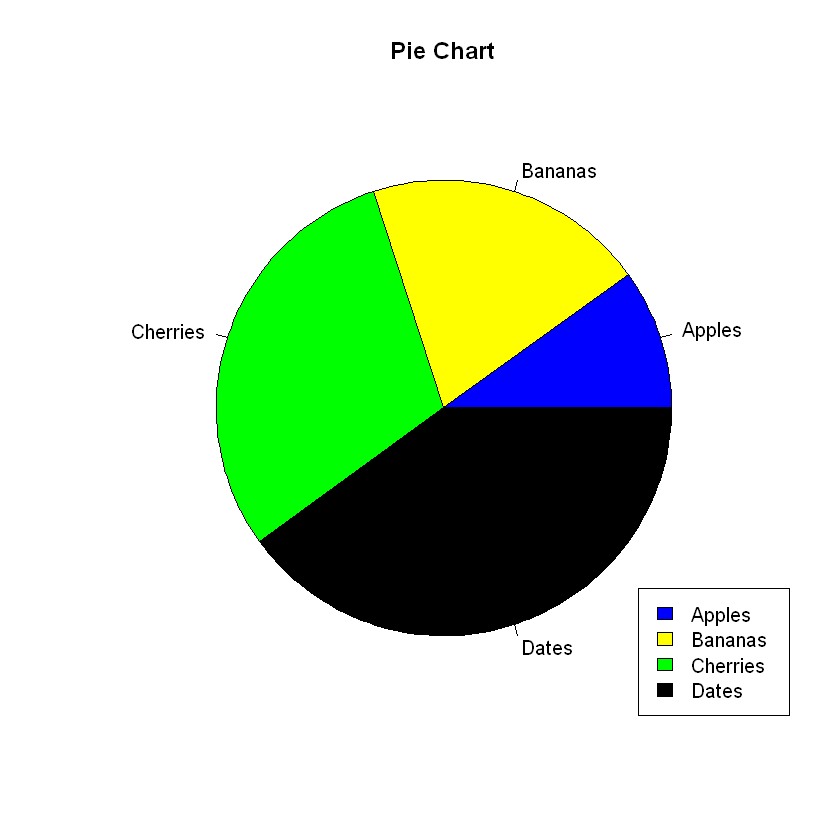

The legend can be positioned as either:

bottomright, bottom, bottomleft, left, topleft, top, topright, right, center

# Create a vector of labels

mylabel <- c("Apples", "Bananas", "Cherries", "Dates")

# Create a vector of colors

colors <- c("blue", "yellow", "green", "black")

# Display the pie chart with colors

pie(x, label = mylabel, main = "Pie Chart", col = colors)

# Display the explanation box

legend("bottomright", mylabel, fill = colors)

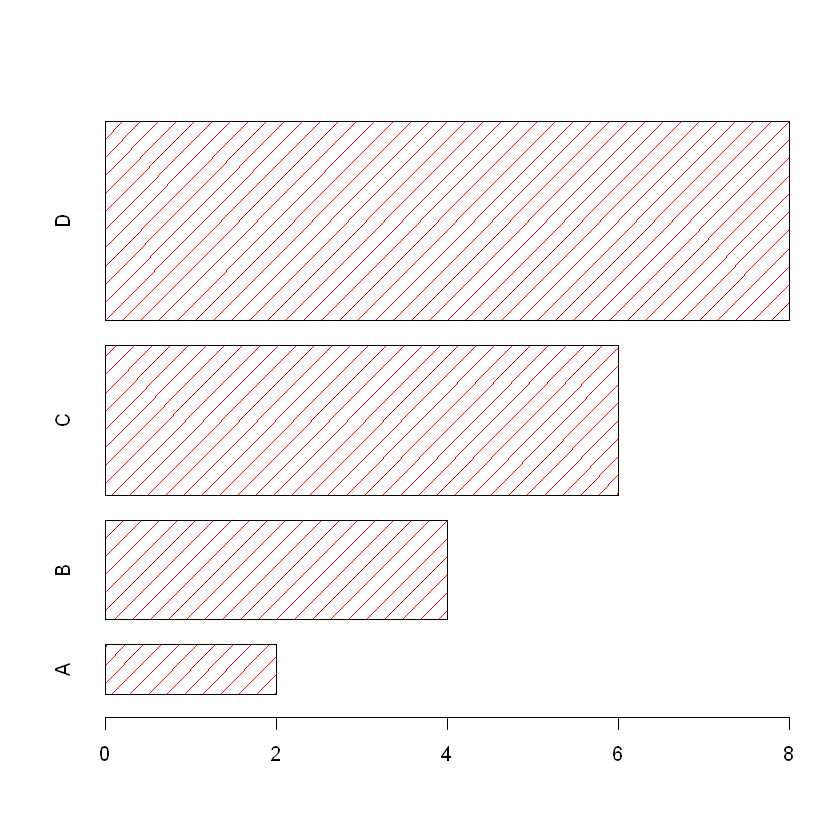

Bars

# x-axis values

x <- c("A", "B", "C", "D")

# y-axis values

y <- c(2, 4, 6, 8)

barplot(y, names.arg = x, col = "red", density = 10, width = c(1,2,3,4), horiz=TRUE)

BASIC STATISTICS

The R language was developed by two statisticians. It has many built-in functionalities, in addition to libraries for the exact purpose of statistical analysis.

Statistics is the science of analyzing, reviewing and conclude data.

Some basic statistical numbers include:

- Mean, median and mode

- Minimum and maximum value

- Percentiles

- Variance and Standard Devation

- Covariance and Correlation

- Probability distributions

Dataset

There is a popular built-in data set in R called mtcars (Motor Trend Car Road Tests), which is retrieved from the 1974 Motor Trend US Magazine.

In the examples below, we will use the mtcars data set, for statistical purposes:

# Print the mtcars data set

mtcars

| mpg | cyl | disp | hp | drat | wt | qsec | vs | am | gear | carb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> | |

| Mazda RX4 | 21.0 | 6 | 160.0 | 110 | 3.90 | 2.620 | 16.46 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Mazda RX4 Wag | 21.0 | 6 | 160.0 | 110 | 3.90 | 2.875 | 17.02 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Datsun 710 | 22.8 | 4 | 108.0 | 93 | 3.85 | 2.320 | 18.61 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Hornet 4 Drive | 21.4 | 6 | 258.0 | 110 | 3.08 | 3.215 | 19.44 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Hornet Sportabout | 18.7 | 8 | 360.0 | 175 | 3.15 | 3.440 | 17.02 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Valiant | 18.1 | 6 | 225.0 | 105 | 2.76 | 3.460 | 20.22 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Duster 360 | 14.3 | 8 | 360.0 | 245 | 3.21 | 3.570 | 15.84 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Merc 240D | 24.4 | 4 | 146.7 | 62 | 3.69 | 3.190 | 20.00 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Merc 230 | 22.8 | 4 | 140.8 | 95 | 3.92 | 3.150 | 22.90 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Merc 280 | 19.2 | 6 | 167.6 | 123 | 3.92 | 3.440 | 18.30 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Merc 280C | 17.8 | 6 | 167.6 | 123 | 3.92 | 3.440 | 18.90 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Merc 450SE | 16.4 | 8 | 275.8 | 180 | 3.07 | 4.070 | 17.40 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Merc 450SL | 17.3 | 8 | 275.8 | 180 | 3.07 | 3.730 | 17.60 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Merc 450SLC | 15.2 | 8 | 275.8 | 180 | 3.07 | 3.780 | 18.00 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Cadillac Fleetwood | 10.4 | 8 | 472.0 | 205 | 2.93 | 5.250 | 17.98 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Lincoln Continental | 10.4 | 8 | 460.0 | 215 | 3.00 | 5.424 | 17.82 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Chrysler Imperial | 14.7 | 8 | 440.0 | 230 | 3.23 | 5.345 | 17.42 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Fiat 128 | 32.4 | 4 | 78.7 | 66 | 4.08 | 2.200 | 19.47 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Honda Civic | 30.4 | 4 | 75.7 | 52 | 4.93 | 1.615 | 18.52 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Toyota Corolla | 33.9 | 4 | 71.1 | 65 | 4.22 | 1.835 | 19.90 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Toyota Corona | 21.5 | 4 | 120.1 | 97 | 3.70 | 2.465 | 20.01 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Dodge Challenger | 15.5 | 8 | 318.0 | 150 | 2.76 | 3.520 | 16.87 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| AMC Javelin | 15.2 | 8 | 304.0 | 150 | 3.15 | 3.435 | 17.30 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Camaro Z28 | 13.3 | 8 | 350.0 | 245 | 3.73 | 3.840 | 15.41 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Pontiac Firebird | 19.2 | 8 | 400.0 | 175 | 3.08 | 3.845 | 17.05 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Fiat X1-9 | 27.3 | 4 | 79.0 | 66 | 4.08 | 1.935 | 18.90 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Porsche 914-2 | 26.0 | 4 | 120.3 | 91 | 4.43 | 2.140 | 16.70 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Lotus Europa | 30.4 | 4 | 95.1 | 113 | 3.77 | 1.513 | 16.90 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Ford Pantera L | 15.8 | 8 | 351.0 | 264 | 4.22 | 3.170 | 14.50 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Ferrari Dino | 19.7 | 6 | 145.0 | 175 | 3.62 | 2.770 | 15.50 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Maserati Bora | 15.0 | 8 | 301.0 | 335 | 3.54 | 3.570 | 14.60 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| Volvo 142E | 21.4 | 4 | 121.0 | 109 | 4.11 | 2.780 | 18.60 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

# Use the question mark to get information about the data set

?mtcars

mtcars package:datasets R Documentation

_M_o_t_o_r _T_r_e_n_d _C_a_r _R_o_a_d _T_e_s_t_s

_D_e_s_c_r_i_p_t_i_o_n:

The data was extracted from the 1974 _Motor Trend_ US magazine,

and comprises fuel consumption and 10 aspects of automobile design

and performance for 32 automobiles (1973-74 models).

_U_s_a_g_e:

mtcars

_F_o_r_m_a_t:

A data frame with 32 observations on 11 (numeric) variables.

[, 1] mpg Miles/(US) gallon

[, 2] cyl Number of cylinders

[, 3] disp Displacement (cu.in.)

[, 4] hp Gross horsepower

[, 5] drat Rear axle ratio

[, 6] wt Weight (1000 lbs)

[, 7] qsec 1/4 mile time

[, 8] vs Engine (0 = V-shaped, 1 = straight)

[, 9] am Transmission (0 = automatic, 1 = manual)

[,10] gear Number of forward gears

[,11] carb Number of carburetors

_N_o_t_e:

Henderson and Velleman (1981) comment in a footnote to Table 1:

'Hocking [original transcriber]'s noncrucial coding of the Mazda's

rotary engine as a straight six-cylinder engine and the Porsche's

flat engine as a V engine, as well as the inclusion of the diesel

Mercedes 240D, have been retained to enable direct comparisons to

be made with previous analyses.'

_S_o_u_r_c_e:

Henderson and Velleman (1981), Building multiple regression models

interactively. _Biometrics_, *37*, 391-411.

_E_x_a_m_p_l_e_s:

require(graphics)

pairs(mtcars, main = "mtcars data", gap = 1/4)

coplot(mpg ~ disp | as.factor(cyl), data = mtcars,

panel = panel.smooth, rows = 1)

## possibly more meaningful, e.g., for summary() or bivariate plots:

mtcars2 <- within(mtcars, {

vs <- factor(vs, labels = c("V", "S"))

am <- factor(am, labels = c("automatic", "manual"))

cyl <- ordered(cyl)

gear <- ordered(gear)

carb <- ordered(carb)

})

summary(mtcars2)

Data_Cars <- mtcars # create a variable of the mtcars data set for better organization

# Use dim() to find the dimension of the data set

dim(Data_Cars)

# Use names() to find the names of the variables from the data set

names(Data_Cars)

<ol class=list-inline><li>32</li><li>11</li></ol>

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘mpg’</li><li>‘cyl’</li><li>‘disp’</li><li>‘hp’</li><li>‘drat’</li><li>‘wt’</li><li>‘qsec’</li><li>‘vs’</li><li>‘am’</li><li>‘gear’</li><li>‘carb’</li></ol>

Use the rownames() function to get the name of each row in the first column, which is the name of each car:

Data_Cars <- mtcars

rownames(Data_Cars)

<ol class=list-inline><li>‘Mazda RX4’</li><li>‘Mazda RX4 Wag’</li><li>‘Datsun 710’</li><li>‘Hornet 4 Drive’</li><li>‘Hornet Sportabout’</li><li>‘Valiant’</li><li>‘Duster 360’</li><li>‘Merc 240D’</li><li>‘Merc 230’</li><li>‘Merc 280’</li><li>‘Merc 280C’</li><li>‘Merc 450SE’</li><li>‘Merc 450SL’</li><li>‘Merc 450SLC’</li><li>‘Cadillac Fleetwood’</li><li>‘Lincoln Continental’</li><li>‘Chrysler Imperial’</li><li>‘Fiat 128’</li><li>‘Honda Civic’</li><li>‘Toyota Corolla’</li><li>‘Toyota Corona’</li><li>‘Dodge Challenger’</li><li>‘AMC Javelin’</li><li>‘Camaro Z28’</li><li>‘Pontiac Firebird’</li><li>‘Fiat X1-9’</li><li>‘Porsche 914-2’</li><li>‘Lotus Europa’</li><li>‘Ford Pantera L’</li><li>‘Ferrari Dino’</li><li>‘Maserati Bora’</li><li>‘Volvo 142E’</li></ol>

From the examples above, we have found out that the data set has 32 observations (Mazda RX4, Mazda RX4 Wag, Datsun 710, etc) and 11 variables (mpg, cyl, disp, etc).

A variable is defined as something that can be measured or counted.

Here is a brief explanation of the variables from the mtcars data set:

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

| mpg | Miles/(US) Gallon |

| cyl | Number of cylinders |

| disp | Displacement |

| hp | Gross horsepower |

| drat | Rear axle ratio |

| wt | Weight (1000 lbs) |

| qsec | 1/4 mile time |

| vs | Engine (0 = V-shaped, 1 = straight) |

| am | Transmission (0 = automatic, 1 = manual) |

| gear | Number of forward gears |

| carb | Number of carburetors |

Print Variable Values

If you want to print all values that belong to a variable, access the data frame by using the $ sign, and the name of the variable (for example cyl (cylinders)):

From the examples above, we have found out that the data set has 32 observations (Mazda RX4, Mazda RX4 Wag, Datsun 710, etc) and 11 variables (mpg, cyl, disp, etc).

A variable is defined as something that can be measured or counted.

Here is a brief explanation of the variables from the mtcars data set:

| Variable Name|Description| |:——–|———:| |mpg|Miles/(US) Gallon| cyl Number of cylinders disp Displacement hp Gross horsepower drat Rear axle ratio wt Weight (1000 lbs) qsec 1/4 mile time vs Engine (0 = V-shaped, 1 = straight) am Transmission (0 = automatic, 1 = manual) gear Number of forward gears carb Number of carburetors

Data_Cars <- mtcars

Data_Cars$cyl

<ol class=list-inline><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>4</li><li>6</li><li>8</li><li>6</li><li>8</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>8</li><li>6</li><li>8</li><li>4</li></ol>

sort(Data_Cars$cyl)

<ol class=list-inline><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>4</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>6</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li><li>8</li></ol>

Analyzing the data

summary(Data_Cars)

mpg cyl disp hp

Min. :10.40 Min. :4.000 Min. : 71.1 Min. : 52.0

1st Qu.:15.43 1st Qu.:4.000 1st Qu.:120.8 1st Qu.: 96.5

Median :19.20 Median :6.000 Median :196.3 Median :123.0

Mean :20.09 Mean :6.188 Mean :230.7 Mean :146.7

3rd Qu.:22.80 3rd Qu.:8.000 3rd Qu.:326.0 3rd Qu.:180.0

Max. :33.90 Max. :8.000 Max. :472.0 Max. :335.0

drat wt qsec vs

Min. :2.760 Min. :1.513 Min. :14.50 Min. :0.0000

1st Qu.:3.080 1st Qu.:2.581 1st Qu.:16.89 1st Qu.:0.0000

Median :3.695 Median :3.325 Median :17.71 Median :0.0000

Mean :3.597 Mean :3.217 Mean :17.85 Mean :0.4375

3rd Qu.:3.920 3rd Qu.:3.610 3rd Qu.:18.90 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :4.930 Max. :5.424 Max. :22.90 Max. :1.0000

am gear carb

Min. :0.0000 Min. :3.000 Min. :1.000

1st Qu.:0.0000 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:2.000

Median :0.0000 Median :4.000 Median :2.000

Mean :0.4062 Mean :3.688 Mean :2.812

3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:4.000

Max. :1.0000 Max. :5.000 Max. :8.000

The summary() function returns six statistical numbers for each variable:

- Min

- First quantile (percentile)

- Median - The middle value

- Mean - The average value

- Third quantile (percentile)

- Max

You can explore also:

- Mode - The most common value

max and min

# max and min

Data_Cars <- mtcars

max(Data_Cars$hp)

min(Data_Cars$hp)

# find the index position of the max and min value in the table:

which.max(Data_Cars$hp)

which.min(Data_Cars$hp)

rownames(Data_Cars)[which.max(Data_Cars$hp)]

rownames(Data_Cars)[which.min(Data_Cars$hp)]

335

52

31

19

‘Maserati Bora’

‘Honda Civic’

mean, mode, median

# find the sum of all values, and divide the sum by the number of values.

mean(Data_Cars$wt)

# If there are two numbers in the middle, you must divide the sum of those numbers by two, to find the median.

# Luckily, R has a function that does all of that for you:

# Just use the median() function to find the middle value:

median(Data_Cars$wt)

# R does not have a function to calculate the mode.

# However, we can create our own function to find it.

names(sort(-table(Data_Cars$wt)))[1]

3.21725

3.325

‘3.44’

Percentiles

Quartiles are data divided into four parts, when sorted in an ascending order:

- The value of the first quartile cuts off the first 25% of the data

- The value of the second quartile cuts off the first 50% of the data

- The value of the third quartile cuts off the first 75% of the data

- The value of the fourth quartile cuts off the 100% of the data

# c() specifies which percentile you want

quantile(Data_Cars$wt, c(0.75))

quantile(Data_Cars$wt)

75%: 3.61

<dl class=dl-inline><dt>0%</dt><dd>1.513</dd><dt>25%</dt><dd>2.58125</dd><dt>50%</dt><dd>3.325</dd><dt>75%</dt><dd>3.61</dd><dt>100%</dt><dd>5.424</dd></dl>

EXERCISES & QUIZ

you can do some more R exercises here

you also can do a simple R quiz here

or, ìf you want, get a R certificate